Phipps Stories

#bioPGH Blog: Duckweed

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

Maybe it’s because I’m a tall individual, but I have a special ironic fondness for the tiny-but-mighty organisms of the world. And if we’re talking both tiny and mighty, few plants quite fit the bill like duckweeds. Measuring mere millimeters in diameter, duckweeds still have complete flowers, tiny roots, and function like a complete photosynthesizing plant (note, you might also spy watermeal here in Pennsylvania, but it doesn’t have roots). Members of the Araceae family, duckweed can be found in freshwater almost globally, they reproduce incredibly quickly, and wherever it is found, it is of particular interest for a few specific research purposes. Let’s explore!

First, let’s talk about how in spite of its tiny size, duckweed can cover ponds. Duckweeds may have tiny flowers, but they don’t quite follow the exact reproductive model of a “typical” flowering plant. For example, when we think of plants with flowers, we generally think of the traditional plant life cycle as something like this: an apple tree’s flowers bloom, pollinators visit those flowers and moves pollen from one flower to another, the pollinated flowers grow apples, apples have seeds, a planted seed grows into a tree, that new apple tree grows blossoms, and the cycle continues. Duckweeds can follow the essence of this model with their tiny flowers (their tiny pollen grains can even be spread by mites!), but they have another trick up their proverbial sleeves. Duckweed proliferate much more commonly through something called vegetative budding; new little duckweeds growing off a parent duckweed.

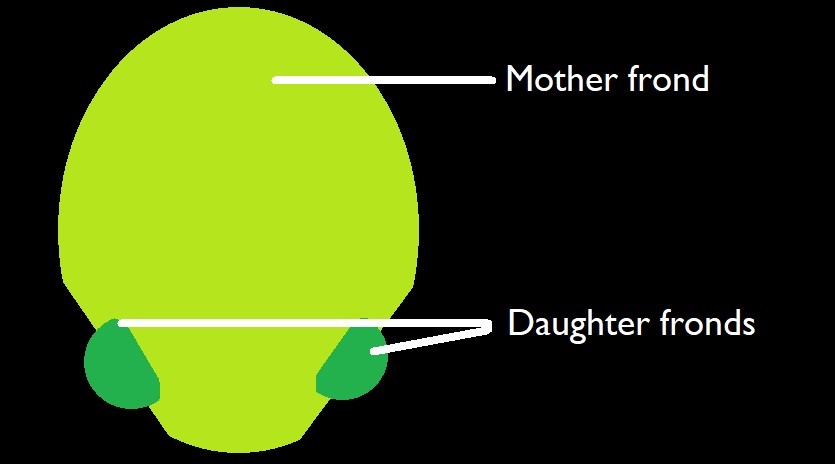

If you look at a single duckweed, the green “body” or “leaf” of the plant is called a frond. At the base of the fronds, each duckweed can produce new little daughter fronds in what is called a frond pouch. As the new little frond grows, it eventually breaks off from the stipe, a little tether holding it to the mother frond. After breaking off, the newly independent frond will start growing news buds itself ( a stylized illustration is below, but for a complete illustration, check out this image from Yoshida et al. 2021.)

New fronds beginning in the frond pouches.

This mode of reproduction allows duckweed to multiply rapidly. In fact, because duckweed can grow so quickly and in such a variety of conditions, it has strong potential as both a possible future biofuel and candidate for bioremediation. As a possible fuel, duckweed is eyebrow-raising because it can, first, quickly take up nutrients from its environment and then, second, convert them into starches just as quickly. These starches would then be useful for humans to harvest as the basis for such fuels as ethanol and butanol. Current work is underway to optimize growing and compound harvesting conditions. That rapid uptake of nutrients is also why duckweed could make a useful bioremediator – duckweed is able to grow in and absorb excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphates from water sources that could otherwise face eutrophication – a phenomenon where excess nutrients from run-off promote the growth of dense algae, phytoplankton, and aquatic plants that stifle oxygen levels and choke out other species. These two avenues of research are of immense economic importance; and just think…the plants in question are small enough to sit on top of a ballpoint pen. As a I noted in the beginning, duckweed may be tiny, but it has some serious might!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: Keep an eye for duckweed the next time you walk near a pond or body of water. Here at Phipps, you can spy duckweed in the lagoon section next to our Exhibit Staging Center or in the smaller pond at Schenley Park.

Resources

US Forest Service – Lemna Minor

Texas A&M University Extension – Common duckweed

Photos: All images from Maria Wheeler-Dubas