Phipps Stories

#bioPGH Blog: Change Over Time

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

February 12 marks the birthday of none other than Charles Darwin. In honor of "Darwin Day," let's learn more about the biologist couple who saw his theories play out before their eyes.

It was 1977 in the Galapagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador. The islands were no stranger to harsh conditions, but that year, an intense drought parched the rocky islands—drying out even the hardiest plants and significantly reducing the food supply for local finch species. A few years later, an unusually rainy season from 1982-83 drenched the islands, allowing plant life to burst and provide abundant food to the feathered inhabitants who had survived the severe drought of 1977.

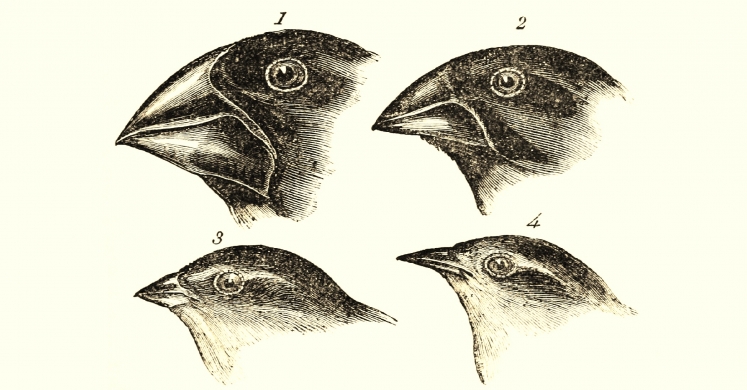

Over the course of those several years, though, something intriguing happened, and two researchers working off the Galapagos Islands, Drs. Peter and Rosemary Grant, were there to document it. When the drought first began, the island’s medium ground finches (Geospiza fortis) quickly consumed the island’s remaining supply of seeds that made up their primary diet. This left larger, tougher seeds as items on the menu, and only the few birds capable of breaking and consuming those seeds — the finches with larger, stronger beaks — survived the drought. Beak size proved to be a heritable trait, meaning that the offspring of the drought survivors also had larger beaks. However, another dramatic series of events came with the exceptionally rainy 1982-83 season when smaller, softer seeds became abundant. This time, finches with smaller beaks had the advantage since they could more easily manipulate and consume the seeds than the finches with larger beaks. Thus, birds with smaller beak sizes became more common in the following years.

What Peter and Rosemary Grant observed was something that would have stunned Charles Darwin himself: evolution in action.

Because this word can evoke a variety of connotations, I want to pause here: the word “evolution” simply means change over time. There is very little in our world that doesn’t change over time in some way or other. Most of us can even look at our own pictures from ten years ago and note a slightly embarrassing evolution of hair styles. The fact that populations of plants, animals, and other living things show changes in the frequency of traits over generations has been incredibly important to species’ survival. Living things need the ability to adapt, and Rosemary and Peter Grant saw these adaptations—evolution—happening in real time. (It is important to note, though: individuals do not change or evolve. The frequencies of traits in a population change.)

Truth be told, though, evolution was actually not the brainchild of Charles Darwin. In his day, evolution was generally considered by naturalists to be an accepted and expected process in nature; the debate was how evolution happened. Darwin’s contribution was a mechanism behind evolution—natural selection. Darwin postulated that for any particular group of organisms, more offspring were produced than could possibly survive and there was variation in those offspring—traits that made some offspring more suited to survive than others. Those traits must be heritable, and the individuals with the most advantageous traits would survive. Ultimately, those with the advantageous trait would produce their own offspring who would also have those beneficial traits. This process is exactly what Rosemary and Peter Grant observed in the Galapagos with their finches—the same species that helped inspire Darwin’s idea of natural selection. They saw environmental conditions (the severe drought) heavily pressure the finches so that a particular trait (the large beak) made some birds more likely to survive. When the pressure changed, and different food sources became available, the frequency of beak types changed over time in the population as some lineages of birds specialized on some food sources over others.

Before Peter and Rosemary Grant, the idea of witnessing evolution was a dream, perhaps achievable only by microbiologists who could grow hundreds of generations of bacteria in a matter of days. Now, however, with over four decades of research on the Galapagos Island, the Grants have seen “Darwin’s finches” evolving on both the physical and genetic level. Though both are now in their late 70’s, professors at Princeton University, they still are active researchers! They also were the precedent for other researchers who have witnessed changes in populations over time—such as North Atlantic killer whales, corals, flowering plants, and even us!

The idea of even slow changes is something that is tough for many of us to visualize, but if organisms couldn’t respond to shifts in their environment, we wouldn’t have the breath-taking diversity of life that we see all around us.

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: Though many of us would be incredibly excited to visit the Galapagos Islands for ourselves, the next best thing might be to hear Peter and Rosemary Grant speak next week at Duquesne University’s Darwin Day—an annual event to mark the naturalist’s birthday in February of 1809. A joint effort by the National Aviary, Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania, and Duquesne University, this year’s Darwin Day will feature the Grants will be speaking on their years of experience, and you may even have a chance to speak with them at the reception to follow. For more information, check out Duquesne’s website.

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Resources

Nature: Evolution Caught in the Act

Grant and Grant 2002: Unpredictable Evolution in a 30-Year Study of Darwin’s Finches

Grant and Grant 1993: Evolution of Darwin’s Finches Caused by a Rare Climatic Event

Grant and Grant 2006: Evolution of Character Displacement in Darwin's Finches

Princeton Alumni Weekly: The People Who Saw Evolution

Photo Credits: John Gould, public domain, and David Adam Kess, CC-BY-SA-4.0