Phipps Stories

#bioPGH Blog: Chickadee Hybrid Zone

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

My backyard bird feeder is a popular hang-out for the local feathered crowd, and on a recent morning, it seemed to play host to quite a few chickadees.

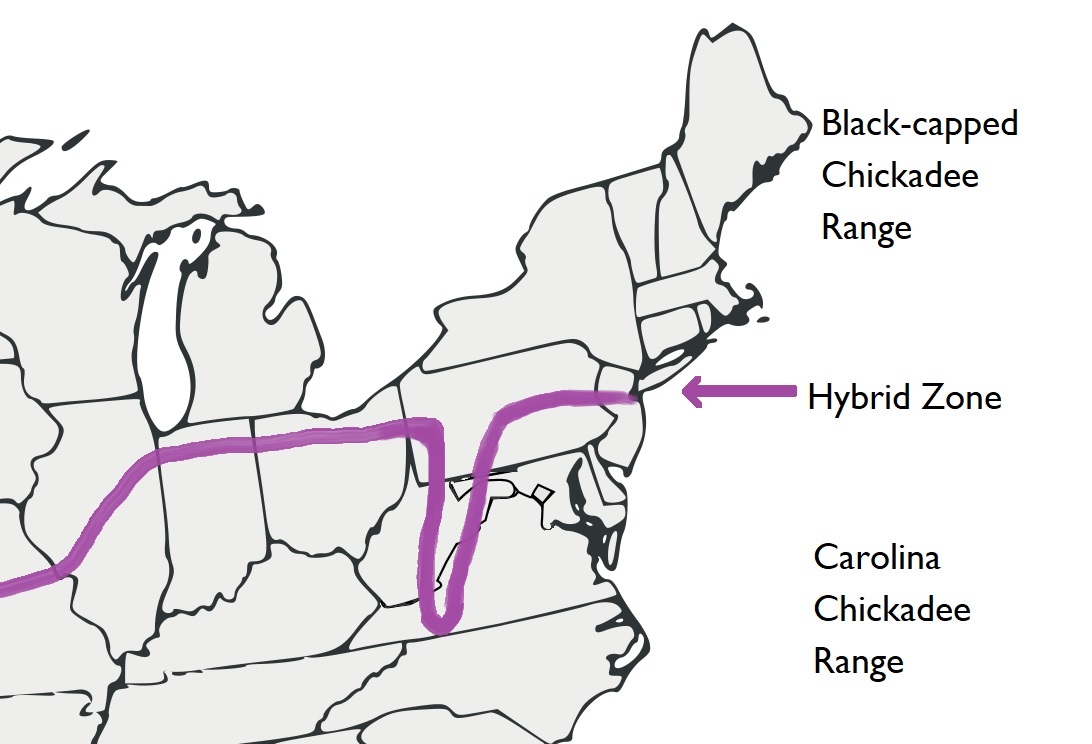

As these little acrobats swooped about between the two feeders and the trees just beyond them, I caught myself referring to them as “black-capped” chickadees; but in truth, since I was only getting quick glances, in that moment I wasn’t sure. Only a few weeks ago, on a local Audubon Christmas Bird Count, we had noted “Chickadee sp.” (Chickadee species) every time we saw or heard a chattering chickadee, rather than mark them as black-capped chickadees, Poecile atricapillus. The reason for the hesitancy is equal parts fascinating and sobering: our area is currently in a hybrid zone of black-capped chickadees and Carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis).

Until the early 2000’s, black-capped chickadees and Carolina chickadees could generally be found in an expected northern “half” or southern “half” of the US, respectively. They tended not to overlap in range except for a thin boundary, a hybrid zone, where both species could be found and some mixing of the two species might occasionally occur. This hybrid zone is not large, averaging only about 21 miles in width. However, as climate changes slowly warms the planet overall, birds have been documented shifting their habitats either higher in elevation or poleward — so for those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, many species have begun shifting northward, including our chickadees. As Carolina chickadees move northward in the face of a warming planet, our black-capped chickadees have responded similarly and have also moved north. Thus, the hybrid zone, which used to be south of us in Pittsburgh, currently overlaps us.

Base map of the US modified from Wikimedia content

The Carolina chickadees, and thus the hybrid zone, seem to have been begun moving northward somewhere between 2000 and 2010 (the earliest paper I could find on it was from 2007), and the species seem to be shifting at a rate of just under a mile per year. I checked in with Chris Kubiak, director of education at the Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania and someone who has watched the skies for years, and he reiterated what I was finding in the literature.

“This hybrid zone continues to push north, and Carolina chickadees move in to our area and displace black-capped chickadees to the north. This is almost completely due to our warming winters (i.e. climate change).”

With two such similar birds, this may seem like an odd thing to notice. But even though black-capped chickadees and Carolina chickadees look similar on the outside, they are two very different birds with different songs, behaviors and variations in plumage. When we take a closer look at their genomes (the collective term for all of an organism’s DNA), they have actually been separate species for a very long time — possibly as much as 2.5 million years. This long-term separation is probably why hybrids between the two seem to encounter some difficulties that the two parent species do not. In a 2020 study, researchers noted that hybrids have a higher baseline metabolism (meaning they have higher energy demands) then their parents, and the hybrids seem to have more difficulty in problem-solving and spatial memory than their parents. So it would seem that for the foreseeable future, our two separate species of birds are best off to remain separate species, though their ranges are shifting.

As I mentioned in the beginning, though, this entire matter is both fascinating and sobering. On the one hand, it’s mindboggling to think of Carolina chickadees collectively moving their species northward, slowly but surely, in response to their environments. On the other hand, it’s sobering to know that this phenomenon is almost entirely due to human impact on our planet’s climate. It’s also important that we recognize how interconnected we are with the rest of the natural world; our fates are intertwined.

Perhaps these chickadees are the twenty-first century version of the canary in the coal mine. We entrusted the lives of friends and family to the wisdom of little songbirds in the past. Maybe it’s time we do that again.

**Climate change is a topic that can feel so daunting that you might think you can’t have an impact. But making a difference right now is easier than you may think. Get started today with these ten actions specially prepared for you by the experts at Phipps. You can also learn more about the science and impacts of climate change with these sources from NASA, NOAA, and Encyclopedia Britannica.

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: If you’re a bird nerd at heart, but maybe aren’t sure how to get involved in meaningful bird conservation efforts, check out the Great Backyard Bird Count coming up in February, a joint effort by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Audubon Society. You can take part in a global community science project from the comfort of your own backyard!

Resources

Photo images: Header, public domain; cover, Maria Wheeler-Dubas