Phipps Stories

#bioPGH Blog: Eastern Box Turtles

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

This Sunday marked the official start of summer, and if you’re a Pennsylvania reptile, summer time is the best time! On my next hike or walk in the woods, I intend to keep an eye out for one little turtle in particular: the eastern box turtle. They have a particularly cool shell, they have fascinating homing instincts and … they’re turtles! An all-around fan favorite. Let’s learn more about them, shall we?

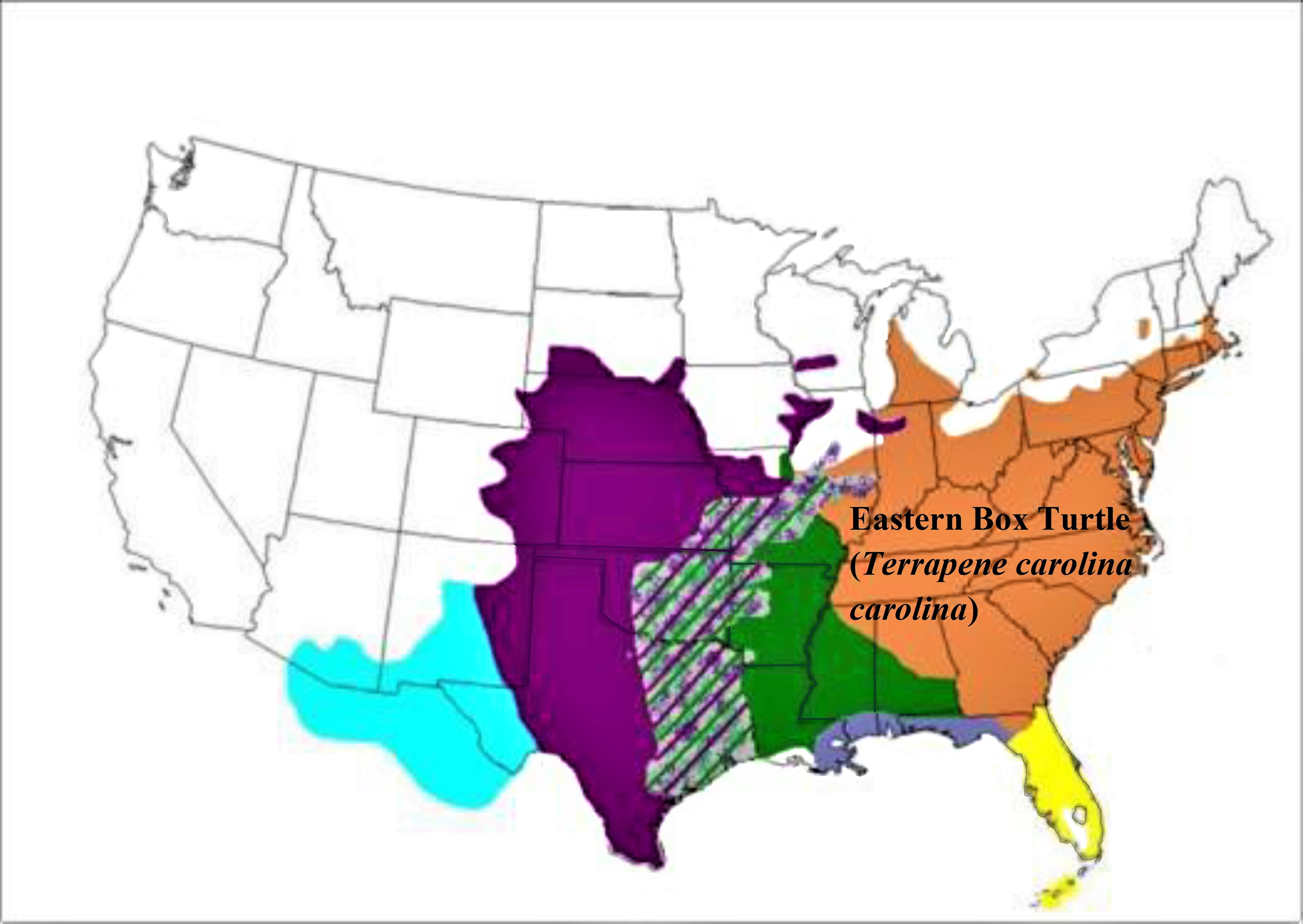

Our local eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina) is a forest-dwelling subspecies of the broader North American species of common box turtle (Terrapene carolina). Check out their range map below:

From Erb 2012, "Range map of box turtle distribution in the United Stated. The eastern box turtle is colored in brown. Other subspecies include the three-toed box turtle (T.c. triunguis, in green), Florida box turtle (T.c. bauri, in yellow), and the Gulf Coast box turtle (T.c. major, in periwinkle). The two western species include the ornate box turtle (T. ornate ornate, in purple) and the desert box turtle (T. ornate luteola, in aqua)." Originally based on a now-closed Davidson College Herpetology Lab Box Turtle map.

Eastern box turtles, like many other turtles, are opportunistic omnivores; in other words, they will eat whatever they can. As juveniles, they often seek out a more protein-rich diet of aquatic insects, but as adults, they may seek out food that … well … doesn’t have to be chased. In adulthood, box turtles often lean more herbivorous, but box turtles will eat leaves, shoots, fruits, insects and other arthropods, and really anything they come across – including carrion.

A fascinating aspect of box turtle biology is their shell! Before I get to that, though, let’s clear up the common myth that turtles can remove their shell or be taken out of their shell; this is just not possible. A turtle’s shell is made of bone covered by a keratin top layer. This bony shell is fused to a turtle’s ribs, which means they cannot discard their shells any more than we could leave our feet at home. And while we discuss their shells, we can note that the top shell of a turtle is called the carapace and the bottom shell is called the plastron. As a general rule, turtles that spend more time on land (such as a box turtle) will have a more highly-domed carapace while turtles that are primarily aquatic (like a painted turtle) have a flatter shell to swim more efficiently. Now, remember that fascinating bit of shell biology? Box turtles can close themselves up in their shell – like a box! Their plastron is hinged, which allows them to “close up” to defend themselves from predators. You may also notice a box turtle’s excellent camouflage; they are dark with yellow flecks to mimic the dappled appearance of sunlight peeking through the tree canopy to reach the forest floor.

Wikimedia user Ineta McParland, CC-BY-2.0

Wikimedia user Fritz GellerGrim, CC-BY-SA-2.5

One other fascinating characteristic of box turtles is their homing instinct. Box turtles tend to stay strictly within their home ranges and if they are moved, they will try as hard as they can to get back home, wherever home may be. Another way to consider this is to say that box turtles exhibit a high degree of philopatry, the tendency to remain in roughly the same area that they were born in throughout their lifetime. And this philopatry seems to be quite strong with box turtles! Studies looking at the effectiveness of box turtle relocation (for example, as conservation strategies) have determined that relocated turtles most likely won’t stay put. Even if they have been moved great distances, they will try to get back home, often putting themselves in very dangerous positions (like crossing streets) to do so.

How do box turtles know where home is, though? The mechanism doesn’t seem to be thoroughly understood, but it is possibly a form of geomagnetism – using the Earth’s magnetic field to navigate. This ability is well documented in sea turtles, though it is notably absent in species like painted turtles. (As an important note for those of us who greatly care about wildlife: This homing instinct is the reason why if you have ever found an injured wild turtle, most wildlife rehabilitation facilities will ask you to document exactly where you found it so it can be returned to the same spot after treatment. Similarly, if you find a turtle somewhere you assume it doesn’t belong, you are still not advised to move it a lengthy distance yourself. Since their home range is usually smaller than a football field, it is very difficult for us humans to guess where that home may be. If we move it away from “home,” we could be endangering the turtle even more. However, if you spot a turtle trying to do something like cross a street, and it is safe for you to assist, move the turtle in the same direction that it is trying to travel.)

Well, as cute as turtles already are, I hope you have a new level of excitement for their unique quirks and abilities! The wild world never ceases to amaze me, and even something as “common” as a common box turtle is no different. So be sure to get outdoors if you can, and keep exploring!

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: If your family is looking to explore the outdoors this summer, there are turtles activities and more through Project Wild's environmental education curriculum! You can search through their list of games and other educational content to spice up your next trip to a state park!

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Photo credits: Cover, National Park Service, public domain. Header, Pexels, public domain.