Phipps Stories

#bioPGH Blog: A Sketch Worth a Thousand Words

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

“Alright,” his gruff voice regained the class’s attention. “Work in pairs, and I am giving each pair a specimen. You will have ten minutes, and at the end of those ten minutes, I want to you to share everything you have learned about your specimen. And leave the specimens in their jar.”

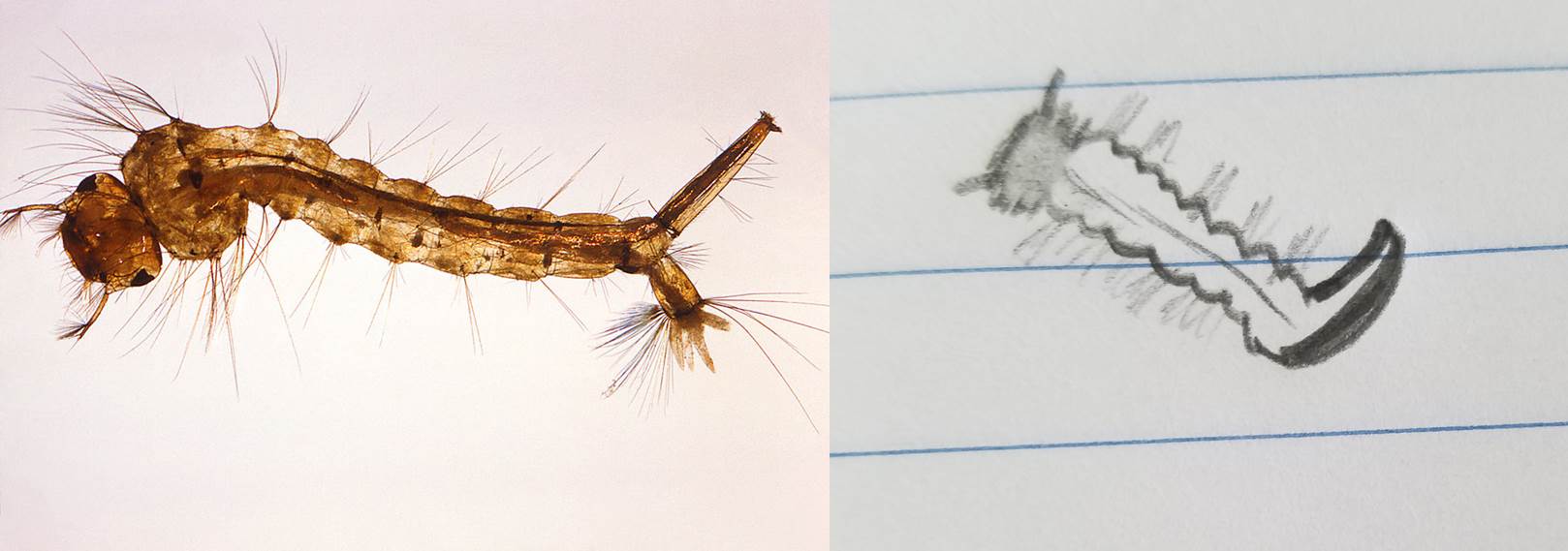

With those basic instructions and a little twitch of his white mustache, he passed out specimen jars that each held some sort of wiggling little…creature. They were tiny and their shape was unfamiliar. Most likely some sort of invertebrate, but insect? Crustacean? The class, a blend of upper level undergraduates and a few biology graduate students looked at each other skeptically. How could they learn something about this creature with no tools but paper and pencil?

As the seconds slowly ticked by into minutes, which seemed to drag even more slowly, the students eventually began writing down simple observations. Body seems to have multiple segments with fuzz? Bristles? Larger head and maybe a bent tail? The longer the students looked at the specimens, the more details became obvious. Here and there across the room, the more daring individuals turned their observations into drawings, preferring to sketch as a more effective way to convey their notes. Meanwhile, the little acrobats in some of the specimen jars bobbed here and there in the water—adding movement style to the list of observations.

Suddenly, the ten minutes were gone.

“Well there you go,” the gruff voice walked through the aisles to look at what the students had taken note. “Ten minutes of observation. Pure observation. You’re all aspiring biologists, how many of you have just stopped and observed something recently?”

Sheepish glances exchanged around the room.

“How many of you just made drawings?”

A few hands.

“Those of you who did, very good. You joined the ranks of all the most famous naturalists in history, who laid our biology foundation for us. And they did it without cameras. If they wanted a realistic picture, they had to observe, they had to look closely, and they had to take in the detail. And then they could draw it. And that’s how they noticed so much. Hardly anyone does this today, not anymore.” The gruff voice shook his head wistfully as he spoke, clearly concerned about the state of natural history in a way that only a person with decades behind them can be.

With his gruff voice and the constant slight scent of pipe smoke, that was one professor I won’t forget. Though his implied worries may seem like hyperbole, he was certainly right about one thing: in a world of technology, and constant busyness, and digital cameras capable of capturing ultra-mega-super-duper pixels, the art of natural history drawings sometimes seems to have been forgotten. It’s a slow process that requires us to pause and look for the most minute of details; and in our daily hurry, many of us miss out on this important part of modern science’s heritage.

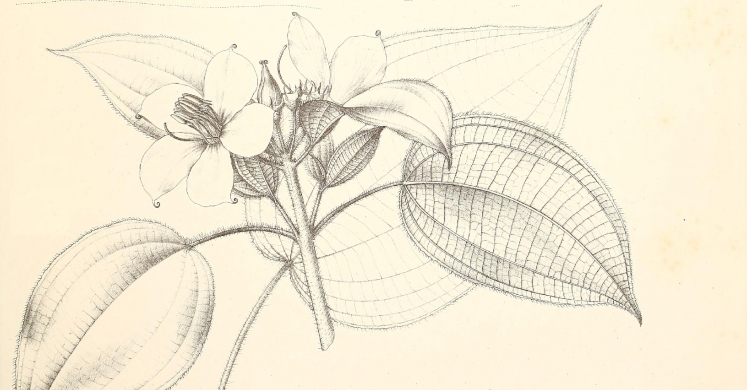

As recently as the last century, sketches and drawings were an essential tool in skill box of a naturalist. In a world without readily available cameras, drawing was the primary means of showing someone this flower or that bird. The great ornithologists Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon both spent significant time and efforts perfecting their own drawing or painting skills before publishing their respective works of natural history. Similarly, Marion Satterlee and Manabu Saito demonstrated tremendous skill in illustrating what is thought to be the first wildflower field guide in the US “How to Know the Wild Flowers” (1893.) Even the US Department of Agricultures relied on the talents of such artists as Mary Daisy Arnold to accurately represent plants and produce in the early twentieth century. In fact, in bygone centuries, if a researcher was not particularly an artist himself, he had to hire one. When Anton van Leeuwenhook first discovered bacteria under a microscope in 1683, he would have hired an artist to create drawings of the micro world for him. In the same vein, academic lore traditionally says that even the Father of Taxonomy and great botanist Carl Linnaeus was not much of an artist himself and would have needed artists to produce images of his specimens.

.jpg)

Ginkgo, an example of an introduction piece by Phipps botanical illustration instuctor Robin Menard

In fact, the importance of drawing as means to truly observe nature is part of why so many events at parks and nature centers (including Phipps’ BioBlitz) often provide art classes or seminars. The art is not truly lost! If you are interested in learning more about this storied skill, you have a few different options. First, Phipps Conservatory offers a number of botanical illustration classes across different skill levels. Currently, the gallery display in the atrium of the Center for Sustainable Landscapes is actually the work of some of the most advanced botanical illustration classes—and they are breathtaking! Another option, if you are interested, is to go on a natural science illustration walk with Apoidea owner Christina Neumann. A bee keeper by day and naturalist at heart, Christina is a wealth of skills and knowledge. Of course, the most peaceful and simplest option: find a few scraps of paper, a pencil, and simply take a walk outdoors. Whatever you choose, enjoy! Keep exploring your world as your immerse yourself in its details.

And in case you were wondering—those little “creatures” we drew that day in class? Mosquito larvae.

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: You don't have to go into the middle of the woods to start observing and sketching - a simple tree or plant in your neighborhood will do. Look closely at the lines, the details, the color. And as you begin, go easy on yourself. New skills are always a challenge, even when they are fun!

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Photo Credits: Monographieen afrikanischer Pflanzen-Familien und Gattungen, Pexels