Phipps Stories

#bioPGH Blog: Caterpillars on the Move!

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

A resource of Biophilia: Pittsburgh, #bioPGH is a weekly blog and social media series that aims to encourage both children and adults to reconnect with nature and enjoy what each of our distinctive seasons has to offer.

The outdoors can be a wonderfully distracting place, as I was reminded earlier this week. While doing some work in my yard, I noticed this caterpillar and how remarkably speedy it was.

I found myself mesmerized by its quick movements, which sent me down the fascinating road of how caterpillars actually move — and it isn’t exactly what we can see at first glance. Let’s explore!

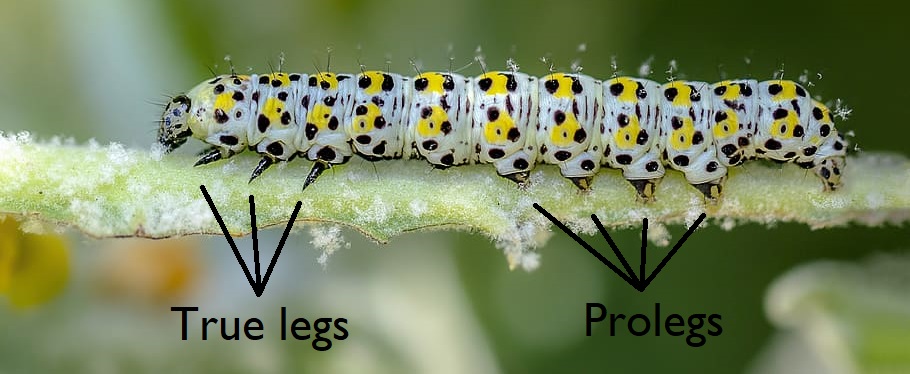

First, a quick review: how many legs do insects have? Six! If you look at a caterpillar, though, they appear to have more than just six legs; but they actually have a combination of true legs and what are called prolegs. The prolegs are a bit roly-poly compared to the true legs, and they do not have joints like the true legs. Depending on the species, the ends of some prolegs are quite similar to little suction cups while others are more like the hooked end of Velcro, which helps the caterpillar stay anchored in place, and indeed most caterpillars rely more on the prolegs for anchoring themselves and the true legs for grasping.

Even though those legs are important to note, they are actually not what propels caterpillars forward. For walking and moving, caterpillars actually rely on a series of internal muscles that contract through the body sequentially, almost like the body muscles are all doing The Wave in a stadium. The motion of those muscles, particularly when pushing off a hard surface, is what moves the body of the caterpillar, and the legs stabilize the body as it moves.

Even more fascinating, a few years ago, a group of researchers discovered something rather interesting about the way caterpillars use their body to propel themselves forward. To fully picture what they discovered, we need to remind ourselves of the “tube” we all have that begins in our mouth, continues to the stomach, through the intestines, and then…“out.” Comprehensively, we can call that long tube the gut. In us humans, with our upright bodies, the gut is a part of our torso, as the other half of our length is in our legs. If you picture a caterpillar, though, that “tube” runs the length of their body. What biomechanics researchers noticed in caterpillars was that as the body is moving, that “tube,” the gut, is propelled forward first, and the rest of the body is catching up, so to speak. The researchers called this process “visceral-locomotory pistoning.”

You can see this played out in a video summary that the authors of this study created:

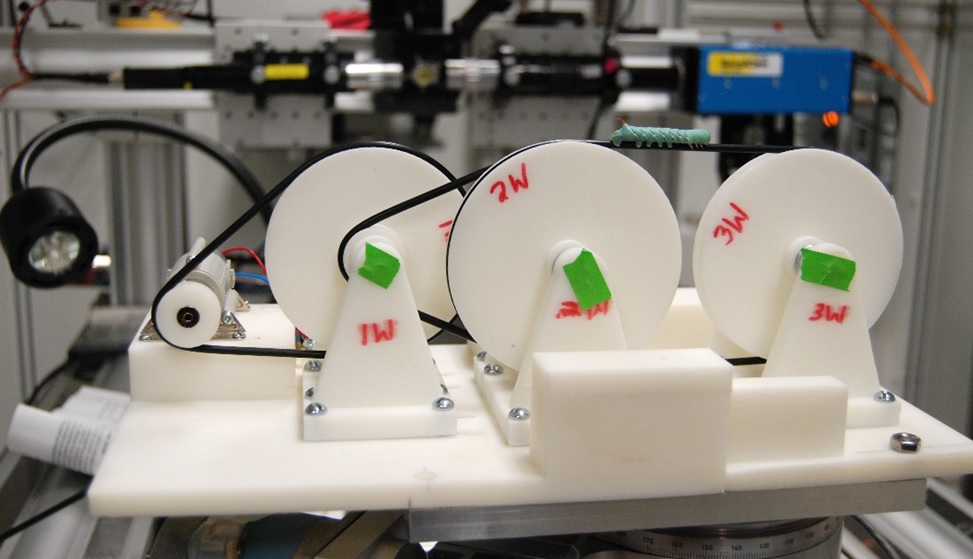

And in case you were wondering how they followed the motion of caterpillars walking – the scientists created a special “treadmill” for the caterpillars:

Note the little sea-green caterpillar on top of the treadmill! Photo courtesy of Dr. Barry Trimmer, Tufts University.

Of course, while learning about how caterpillars carry themselves from point A to point B is fascinating in and of itself, there is another level of value to researching movement in nature, and this work with caterpillars is no exception. Nature has many clever designs, and we humans have been able to capitalize on the mechanics of movement for our own technology. For example, if you remember a while ago, we discussed pileated woodpeckers and their ability to protect their brains from damage while drumming on trees; the technology for airplane “black boxes” was actually improved by studying the skulls of woodpeckers! In this study with caterpillars, the results are useful for the future of soft-bodied robotics.

The next time I watch a caterpillar crawl, I will certainly be taking a closer look at the details of their walking patterns, and now I want to know the other hidden wonders of the wild world in movement! There is so much to learn, we just have to keep exploring!

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Dr. Michael A. Simon for his assistance with this post and to Dr. Barry Trimmer for the treadmill photo.

Connecting to the Outdoors Tip: While caterpillars are fascinating little creatures, it's always best to leave them alone in the wild - especially if they are hairy! Those little hairs can irritate your skin or get rubbed into your eyes, or they can cause allergic reactions. Always best to let living things be.

Continue the Conversation: Share your nature discoveries with our community by posting to Twitter and Instagram with hashtag #bioPGH, and R.S.V.P. to attend our next Biophilia: Pittsburgh meeting.

Resources

Simon et al. 2010: Visceral-Locomotory Pistoning in Crawling Caterpillars

NPR Gut Check: How Do Caterpillars Walk?

Simon et al. 2010: Motor patterns associated with crawling in a soft-bodied arthropod

The Ohio State University: Is it a Sawfly Larva or a Caterpillar?

Brackenbury 1997: Caterpillar Kinematics

Photo credits: Cover, public domain; header, Maria Wheeler-Dubas; marked caterpillar leg image, public domain.