Phipps Stories

Environmental Justice: An Introduction

Phipps recognizes and acknowledges that many organizations and people are already strongly dedicated to bringing equity and justice to this issue. Our goals with this new blog series are to support those who have already spent time and resources in this area, amplify marginalized voices, and report on the ways systemic racism impacts health. Thank you for joining us for this critical conversation.

In Houston, Texas, in 1979, a young Dr. Robert Bullard was asked to help collect data in a lawsuit levied against a waste company that wanted to establish a significant landfill next to a primarily Black community. In this process, Dr. Bullard discovered that although Black residents made up only 25% of the city’s population at the time, 100% of the city’s landfills and most of the city’s waste incinerators were directly situated next to predominantly Black communities. The result was that these communities were disproportionately exposed to pollution that others – notably, predominantly white communities – were not. Though the case against the new landfill was ultimately lost, the experience poignantly impacted Dr. Robert Bullard and decades later earned him a title of recognition as the “father” of a new field of study: environmental justice.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” However, in practical use, the term environmental justice has expanded to capture issues such as flooding, green space, air pollution, food, and other issues that transcend national borders such as climate change (Walker, 2012, pp 17).

We can see environmental injustice when we note that marginalized and low-resource communities often bear the heaviest burden of negative environmental impacts, such as exposure to air pollution and contaminated land and water sources. Though environmental health is a global issue, numerous controversies in the U.S. alone shed light on this ongoing struggle. In 1987, a landmark study called “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States” found that American commercial hazardous waste facilities were most commonly established near Black and Latinx communities. A 2011 study demonstrated how Appalachia’s history of a mono-product economy in coal mining resulted in polluted waterways, poor air quality and higher mortality rates than national averages — a complicated interweaving of socioeconomic disparity and environmental degradation. Even more recently, the ongoing Dakota Access Pipeline struggle arose when the originally proposed pipeline was rerouted to avoid running under the primary drinking water of Bismarck, North Dakota and instead threaten the drinking water of the Standing Rock Sioux’s reservation.

Photo: Lars Plougmann, CC BY-SA 2.0

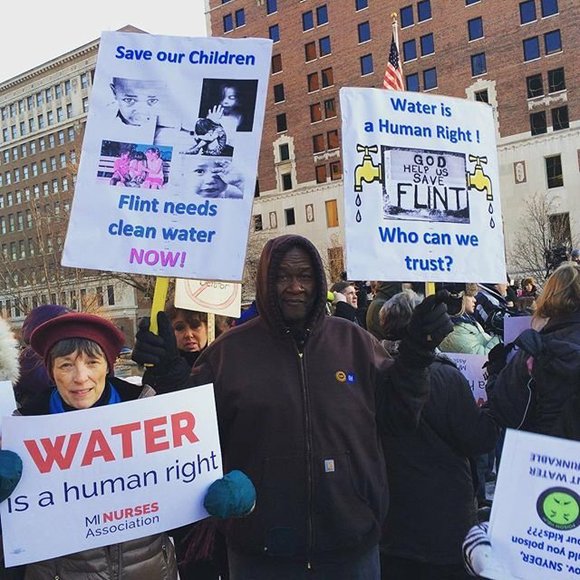

Since the publication of “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States,” numerous scientific publications have described the greater burdens of environmental hazards in communities of color. In 2012, a study by Yale University researchers noted that exposure to airborne particulate matter varied significantly by race. A 2018 study by the EPA further revealed that exposure to particulate matter, an air pollutant linked to asthma, low birthweight, heart attacks and high blood pressure, are associated with race. Black people are 1.5 times more likely to be exposed to particulates than whites and Hispanics* 1.2 times more exposure than non-Hispanic whites. Research has also shown water quality varies widely across race and socioeconomics, as in this 2017 study which that noted low-income Black and Hispanic communities are most likely to have poor-quality drinking water, this 2019 study showing disproportionately high nitrate concentration in the drinking water of primarily Hispanic communities, and the ongoing crisis in Flint, Michigan.

Photo: Shannon Nobles, CC-BY-SA-4.0

In fact, it is critical to note that communities of color are often disproportionately impacted by environmental injustices.

“Although it seeks to address equity and provide environmental protection for all, environmental justice is characterized by a complicated history of political, social, and economic interactions,” says Dr. Plaxedes Chitiyo of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Geography, Environment, & Sustainability department (recently of Duquesne University, Center for Environmental Research and Education). “Its origins can be traced back to the 1960’s and 70’s civil rights movement and it gained prominence with Warren County residents protests siting of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) landfill in North Carolina in 1982.”

Dr. Chitiyo goes on to note that because it tapped into civil rights movement, issues of race and racism were introduced in the environmental debate resulting in Dr. Benjamin Chavis, a civil rights activist coining the term environmental racism in response to the Warren County toxic waste dump (NRDC, 2020). Today, the term environmental racism refers to any environmental policy, practice or directive that differentially affects or disadvantages (intentionally or unintentionally) individuals, groups or communities based on race or color (Bullard, 1999).

Dr. Plaxedes Chitiyo speaking at Phipps' Nature of Place Symposium, February 2020

Phipps Conservatory believes that human and environmental health are inextricably connected, so it important for us to acknowledge the disparities in the health and well-being of our neighboring communities. In this new blog series, we will explore different facets of environmental justice and highlight the people and organizations already working in this field. We will also engage in conversations around the long-term impacts of environmental injustice, including issues local to Pittsburgh, and what actions we can all take to inspire change. We claim neither expertise nor innocence, only a willingness to listen, learn and take action, and we will do so in cooperation with the experts in our community. We believe it is most important that we all learn together so that we can improve together.

Taking Action Together: In this section, we will share advice from community members about best practices and ways to get involved in this matter. Right now, our best actions are to listen and learn to understand. All of the references from the post are listed below – take some meaningful time for a deeper dive and please feel free to include your own resources in the comments below.

*We use the term Latinx for accuracy, but in order to most honestly report the findings of different studies, we will use the term “Hispanic” where original research authors did.

Image Credits: Cover, Susan Melkisethian CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; Header, Mark Dixon, CC BY 2.0

Resources

Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States

Environmental Inequality in Exposures to Airborne Particulate Matter Components in the United States

Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status

Class, Race, Ethnicity, and Justice in Safe Drinking Water Compliance

The Flint, Michigan, Water Crisis: A Case Study in Regulatory Failure and Environmental Injustice

Bullard, R. D. (1999). Dismantling environmental racism in the USA. Local Environment, 4(1), 5-19.

Walker, G. (2012). Environmental Justice: Concepts, evidence, and politics. Routledge