Phipps Stories

A Day in the Life of a COP30 Attendee

I’ve heard the experience of attending the global climate conference described in many ways by other attendees:

- It’s like trying to drink from a firehose.

- There is everything happening and nothing happening at the same time.

- You want to attend everything, everywhere, but aren’t really needed anywhere. The amount of choice is overwhelming.

In my experience, attending COP30, the Conference of Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is all these things; it’s an experience like no other. It’s feeling both exhausted and energized, your feet aching, hope and frustration held in each hand, with your community in mind and your own determination to do better driving you forward to keep giving it your all each day. I was lucky enough to attend COP30 with our Youth Climate Advocacy Committee (YCAC) youth leader Marley McFarland, a Chatham University student majoring in sustainability and creative writing. Marley has been working on climate action for many years, even before she joined the YCAC in 2021 during its founding year. She has been a champion of youth climate action in the Pittsburgh region, working on initiatives developing and teaching environmental education lessons, hosting sustainable art and fashion workshops and shows, compiling climate literary works, planning climate events, and supporting and mentoring many other youth-led initiatives. Marley was definitely the correct person to attend COP30 alongside.

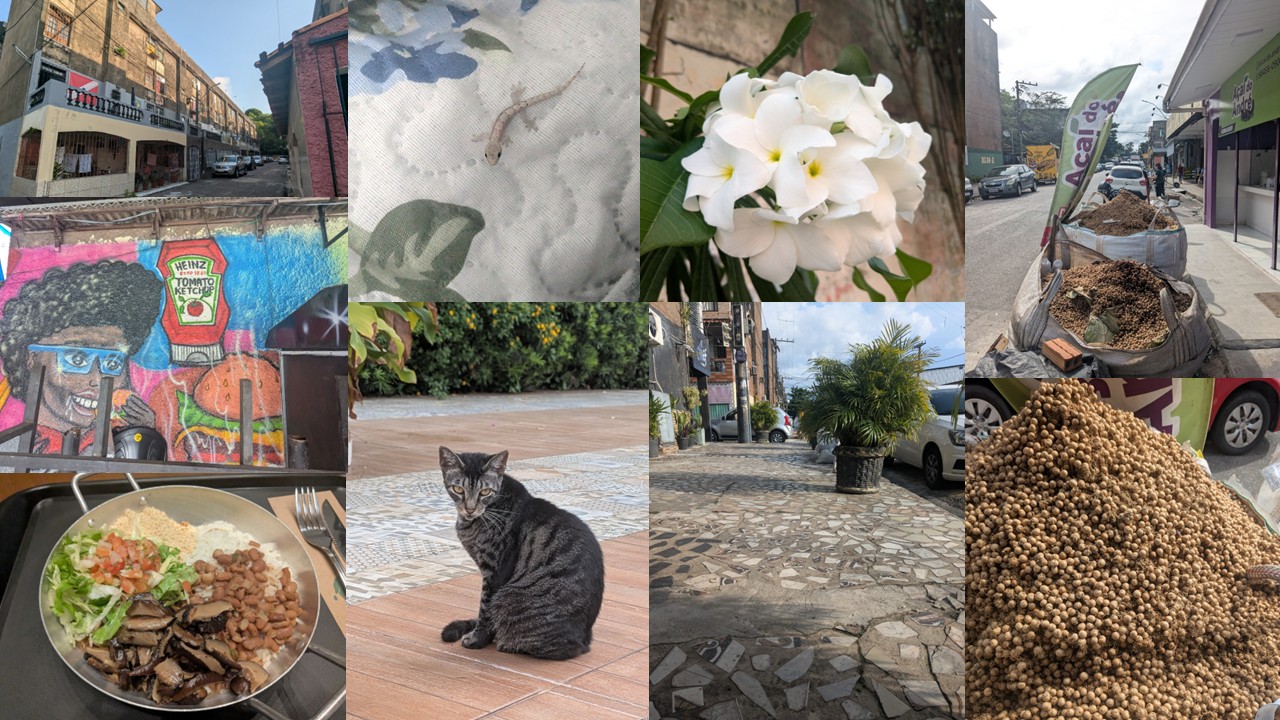

This year, COP was held in Belém, Brazil, a city sitting at the mouth of the Amazon River and the edge of the Amazon rainforest. It is full of vibrant culture, biodiversity and wildlife (like the lizard in my Airbnb bedroom), beautiful music that floated through my windows every night, and kind, warm, welcoming people that helped us across language barriers. While it took some time for me – someone raised in heavy lake-effect snow – to adjust to the 90-degree heat with necessary cold showers twice a day, hosting COP30 in the heart of the Amazon was crucial to keep nature and climate justice at the forefront of climate negotiations. Belém, Brazil was perfectly poised to highlight the importance of indigenous rights, deepen attendees’ biophilia – our innate connection to the natural world, and ground ourselves in all that we’re trying to save.

So what was our experience like, day-to-day?

Each day started with a quick cold shower, a warm “bom dia!” to our downstairs neighbor Miss Regina, and a mile walk down the streets of the Souza neighborhood. Even early in the morning, the streets were lively. Shopkeepers opened their stores, older residents of the neighborhood greeted each other (and us!) on their morning strolls, and motorcycles weaved around cars and pedestrians. On our street, we passed huge bushels of acai fruit, beautifully tiled patios, roaming cats and the familiar sight of a Heinz ketchup bottle painted on a wall. There were many open-air clothing shops, grocery stores, and food stands of all kinds: ice cream, pizza, and many local treats both sweet and savory. By the end of our street, we were sweaty and dreaming of delicious Brazilian food.

The entrance into COP was always bustling. We approached the entrance to chants of “Bom dia! Bom dia! Bom diiiiiaaa!” from the COP30 volunteers. Indigenous people sold hand-made trinkets outside the Blue Zone gates and people from many different organizations stood with signs advocating for everything from climate justice to vegetarian diets. Inside, we went through airport-style security, scanned our Blue Zone badges at the gate and walked past the endless pavilion spaces to the large screen displaying all the negotiations, plenaries, side events, and any other events happening that day. From there, we plotted our day: often daily constituency meetings in the morning, followed by hours of notetaking in the negotiation rooms, a policy debrief in the evening, and many other side events, pavilion talks, and demonstrations in between.

YOUNGO Spokes was one of the best ways for us to catch up on all the negotiation news first thing in the morning. YOUNGO is the official children and youth constituency of the UNFCCC. Each morning, youth from around the world would gather to share updates and urgencies. People shared needs for other youth at bilateral meetings with Parties who are friendly to youth, such as G77. There were opportunities for youth to enter the High-Level Plenaries by offering to take notes. Lots of youth events and demonstrations needed support. Many working groups asked for help from anyone who had capacity. We learned a lot about what was going on in different negotiations from these meetings. In one meeting, the Nature working group updated us that during a negotiation, several Parties said they didn’t understand the text and didn’t have time to learn it. They ended up withdrawing the informal-informal meeting (where they draft text) and replacing it with a presentation to negotiators to get them all on the same page! We also learned about funny moments at COP: one day, the Energy Working Group tried to bring in a four-piece orchestra and getting it through security was chaos!

The COP Secretariat joined one YOUNGO Spokes meeting to explain her role and offer advice on how to engage with negotiators. The Secretariat supports the COP Presidency and the Parties by organizing meetings they want to hold and aiding every negotiation through notetaking, compiling the text, and supporting the process. She informed us that Parties often use one negotiation against another as a bargaining chip.She advised us to go up to talk to Parties kindly and ask about their perspectives and goals to gain understanding because their work is very hard. She suggested ways to demonstrate by calling out issues while encouraging solutions, offer wording for the text we did not like, and work with other NGOs on collective actions.

After Spokes, Marley and I would head to our first negotiation. We followed Gender and Climate Change negotiations primarily, Loss and Damage secondarily, and observed a few other negotiations to get a sense of what was happening at COP overall. Walking through the crowded hallways where we dodged people rushing in all directions, we often spotted friends we’d made from earlier in the week: fellow U.S. college students, climate professionals from many different orgs, and youth from South Africa, the Philippines, Mongolia, Vietnam, the UK, Uganda, and many other places, all caught up in a swirling sea of people. We were lucky if we got to say a quick hello before being pulled away by the tide.

Negotiations can often be dry and technical, but the Gender and Climate Change negotiations were interesting from the very beginning. These negotiations built on the 2014 Lima Work Programme on Gender (LWPG), which acknowledged the disproportionate impact of climate change on women, aimed to advance gender balance, and called for gender responsive climate policy and action. For anyone unfamiliar with this topic, here is an article from the UN explaining why the connection between women and climate action is so crucial.

The Convention currently defines gender as binary, which several Parties disagreed with. This led to Paraguay adding a footnote to state their Party’s definition of gender, which then started a waterfall of footnotes in response. Adding footnotes may not seem like a big deal, but footnotes are a threat to the multilateral process because it shows divergence. So, while some Party were arguing with other Party over the definition of “gender,” still other Party were arguing with the entire room about the inclusion of footnotes. The UK even went as far as to say it was a “red line” for them if footnotes were included at all, meaning they would not agree to the entire text. In response, Paraguay said it was a red line for them to have a text where their definition of gender was not represented.

The Gender and Climate Change negotiations continued is debates over language such as “Gender- and age- disaggregated data,” “Girls in leadership roles,” “Environmental and human rights protectors” and the agreed-upon language “Gender responsive” v.s. the Russian Federation’s weakened version “with a gender perspective.” As youth, we were highly in favor of including language around girls in leadership roles and gender- and age- disaggregated data, which is crucial for showing the disproportionate impacts and burdens of climate change on youth and women. While girls in leadership roles were hardly mentioned in the final text, gender- and age- disaggregated data was included many times in the Belém Gender Action Plan. Additionally, the phrase “environmental and human rights defenders” was cut to just “environmental defenders” out of concern that “humans rights” was “too political.” But “gender-responsive” prevailed in the final text, which was a win.

More COP30 Reading: